Solar Energy Illuminates Darkest Parts of Africa

This is Part One of a five-part series on Renewable Energy for Africa

Continue to Parts: 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5

Countries across Africa are enduring power generation crises, and others will in the near future. To avoid them, some are investing billions of dollars in new coal-fired power plants that harm the environment, potentially dangerous nuclear energy projects and huge hydroelectric schemes that cut people off from water sources.

Environmentalists and clean power proponents argue that the money would be far better spent on much smaller, but ultimately further reaching, renewable energy ventures concentrated at village and town level.

A pioneer in solar energy, Bob Freling, said big, conventional power projects often benefit only urban populations, while hundreds of millions of rural Africans continue to languish in poverty caused largely by a lack of electricity.

For almost 20 years, as director of the Washington DC-based Solar Electric Light Fund (SELF) NGO, Freling has helped provide access to clean, sustainable solar energy to more than a million people in 20 developing countries.

He’s known internationally as “The man who wants to light up Africa” because of his conviction that access to electricity is a basic human right, not a privilege. Freling advises world leaders and the United Nations on development through solar power.

In 2008, Queen Noor of Jordan presented him with the King Hussein Leadership Prize in honor of his efforts to promote sustainable development, human rights, equity and peace.

The energy gap

In an interview with VOA, Freling said, “It makes me sad when I look at that satellite image of earth at night and see Africa still essentially in the dark. The fact that so much of Africa is still without electricity is a huge psychological burden for the continent. It’s also a physical burden counting against Africa’s progress.”

He maintained that lack of power leads to poor quality of life, children having no futures and to disease and death. “It prevents kids from reading and studying at night. It forces families to breathe in the carcinogenic fumes of kerosene lanterns and to suffer from the fires that are caused by kerosene lamps falling down or exploding – fires that maim and kill literally thousands of people every year.”

Without electricity, Freling explained, many Africans can’t earn money. “In terms of their economic lives, their productive day is done as soon as the sun goes down. There’s very little they can do to help grow their economy when there’s no access to power,” he said.

Without power, they can’t pump clean water, forcing them to trudge long and dangerous distances in search of water and wood for the fires needed to purify it. To do these basic chores of survival, many African children are forced to drop out of school.

“Without energy, these folks will not be able to experience significant improvements in their health and education. When you get right down to it, energy is the foundation for life,” Freling said.

Photovoltaic revolution

Freling’s NGO electrifies rural areas with what he called “stand-alone photovoltaic systems.” Arrays of solar panels use cells known as photovoltaics to convert sunlight into electrical current. A battery stores the electricity and, when discharged, powers lights and other appliances. The batteries are large enough to provide several days of electricity if overcast weather prevents recharging.

“It’s one of the most gratifying parts of my job – the reactions of people who are able to flip a switch and have electric light come on for the first time. It’s a very profound experience, for them as well as for me,” Freling said. “It’s amazing to see a whole previously unknown world of opportunity suddenly open up to them, with just one light bulb coming on. To see peoples’ faces, the sheer joy on them, when they realize that they will now be able to read at night, is indescribable.”

The SELF NGO has used microfinance arrangements to enable individual families to pay for their electricity units. A photovoltaic energy system designed for home use usually costs between $550 and $650.

Freling explained, “In the long run these solar systems work out much cheaper than people having to buy kerosene and candles every week their whole lives, and they’re safe and environmentally friendly…. Families have usually paid for them within two to three years.”

SELF initially focused on electrifying individual homes. But, in the early 2000s, Freling decided to “go bigger.”

“As much as I believe in bringing light to a family, I recognized that the technology we were using had potential way beyond household lighting, because the same solar panel that is used to light up a house can be used to pump water, or power a health clinic or a school.”

So in recent years SELF has concentrated on powering entire villages across Africa – revolutionizing life for many thousands of people.

Northern Nigerian example

The NGO’s flagship “whole village” project is in northern Nigeria. The country’s vast oil wealth hasn’t benefited the region’s inhabitants. Most don’t have electricity. They live in mud and thatch homes and survive by growing crops among desert grasslands. They cook over wood fires; kerosene lamps provide light; and clean water sources are far away.

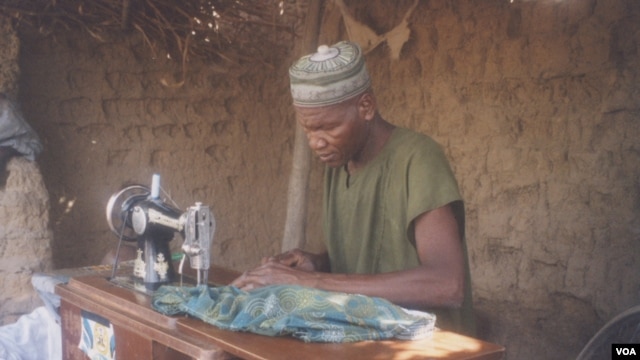

But SELF’s solar technology has transformed the lives of 7,500 people in northern Nigeria. “We electrified three villages in the northern state of Jigawa and in each of the villages provided power for a number of homes, a school, a health clinic, a mosque, water pumping systems, street lighting, and even a microenterprise center that would power a number of small businesses in the village,” Freling explained.

Businesses selling food have sprung up under streetlights, and people are earning money for the first time in their lives. Illiterate adults are learning to read and write at night classes. Children have access to computers – a previously unattainable but vital part of modern education.

As in other countries, like Burundi, Lesotho, Malawi and Rwanda, the photovoltaic solar energy provided by SELF has for the first time electrified clinics. In Jigawa, doctors are now able to treat patients at night, and vaccines can be refrigerated – allowing more children to be vaccinated against potentially fatal sicknesses and facilitating round-the-clock treatment of people with serious diseases such as HIV, malaria and cholera.

African creativity

Something happened in one of the Nigerian villages that Freling said illustrated the “supreme ingenuity” of Africans that he’s come to respect over the years.

At Wawan-rafi, farmers irrigate their crops with water from a river. Traditionally they’ve watered their fields using hollow gourds – a very slow and labor intensive process that limited production severely.

“It was one of the villagers who came up with the idea of putting an array of solar panels on the back of a cow. The villagers wanted something that was portable,” said Freling.

So, in cooperation with the people of Wawan-rafi, SELF designed a cattle cart equipped with fold-out solar modules of extreme strength that could power a water pump and be moved from field to field. It allows farmers to irrigate their crops efficiently and grow much more food than ever before.

Freling said, “We want to work with the community to come up with solutions that meet their needs. They’re very intelligent; they’ve very creative people. You give them half a chance and I can assure you they will come up with very innovative solutions. They just need a little bit of help.”

He maintained that access to electricity that allows development fosters peace, especially in areas prone to religious and political extremism, such as northern Nigeria.

“When you have people who are deprived of basic opportunities in life, they become disenfranchised. Often, those vacuums can be filled by people promising certain things. The more you can provide a better life for people in developing countries, the better chance we have of preventing them from being attracted to extremist organizations [like al-Qaeda affiliated Boko Haram in Nigeria],” said Freling. “I think that one of the greatest antidotes to this kind of terrorism is to make life better for people.”

Unique irrigation in Benin

In the Kalalé district of northern Benin, more than 100,000 people live in 44 villages. Before SELF entered the area, none of the inhabitants had electricity. There are also no schools or hospitals there. But the villagers’ main concern is chronic food shortages.

Kalalé borders the arid Sahel region and has a very long dry season. Freling recalled his first visit to the district in 2007. “Essentially no food was grown; diets were very restricted; malnutrition was widespread. You’d often see these kids with the distended belly, a telltale sign of kwashiorkor, a form of malnutrition.”

SELF implemented a groundbreaking method to end food insecurity in the area. “We combined solar water pumping with drip irrigation, allowing farmers to grow food year round,” said Freling.

Drip irrigation systems use gravity to draw water from reservoirs through pipes. But power is needed to pump water to the reservoirs. Usually, the power is provided by diesel engines, but Freling wanted the system in Benin to be environmentally “clean” and energized by the sun.

SELF’s “Solar Market Garden” prototype was successful. A solar pump now draws water from a stream that flows constantly to fill an irrigation dam in the Bessassi area. At Dunkassa village, water is pumped from the ground.

Freling described the project as a remarkable success. “You go back and you see these fields filled with leafy green vegetables…. What I noticed the first time I went back was how the women had physically filled out. You could visibly see a difference in the health of the people in the village. They were eating well.”

Three Solar Market Gardens enabled the villages of Bessassi and Dunkassa to produce almost two tons of fresh produce every month. “For the first time in their lives, they weren’t hungry. On top of that, they were making money. I would say about 20 percent of the produce was being consumed by the [local] families, the rest was being sold to market,” said Freling.

As well as feeding them, the electricity that allowed the villagers to irrigate their crops opened up the world of business to them. Suddenly, said Freling, they could afford clothes for themselves and their children and medicines without which death rates had previously spiked.

Costs and training

According to Freling, a Solar Market Garden - sometimes including photovoltaic power systems - managed by a village collective typically costs about $25,000. “That sounds like a lot but they pay for themselves within a few years [through profits made from having access to power],” he said. “We’ve been able to demonstrate in many places in Africa how much cheaper it is to provide electricity with solar power rather than traditional diesel generators.”

Freling explained that while the upfront cost of a generator is low, its operating and maintenance costs are high, with spare parts being expensive and rare in many parts of Africa. He added that diesel fuel is often not available in isolated regions of the continent.

He continued, “With photovoltaics, the upfront cost is higher but there are no fuel costs and much less maintenance costs. So over time you’ll spend a lot less money on these solar systems.”

SELF ensures that communities have thorough knowledge of the solar energy systems they use. Its experts help locals design, install and maintain the technology. Freling said they’ve trained many Africans as solar technicians.

“We’ve had great luck in finding people – in some cases with no more than a fourth, fifth grade education – but they’re smart, they’re intuitive, they’re good with their hands and they become great solar technicians. We’re very proud of some of the folks that we’ve been able to train in Africa to become solar champions in their own right,” he said.

MDGs to fail without electricity

Freling and his organization have done plenty to bring electricity to Africa. But he said the many millions of Africans who continue to “decay in the dark” now need help from figures far more powerful than he.

“I am very, very impatient for the continent to make a commitment to bring in modern clean energy services to the people. It’s within our power now. But a lot depends on the political will of African leaders. That will be the most important determining factor in whether or not African populations have access to energy,” he said.

Freling called for a new level of commitment from African leaders, for them to “embrace the idea of universal energy access” and to recognize that having electricity is a basic human right.

He urged the leaders to make the political commitments necessary to put in place the regulatory, legal and financial environments needed for the private sector, civil society and local governments “to cooperate towards creative solutions that will enable people to have access to clean energy services.”

Without the large-scale “green” electrification of the developing world, Freling warned, each of the U.N.’s eight Millennium Development Goals – including the end of poverty, hunger, widespread death from disease and lack of education – will fail.

Continue to Parts: 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5

Countries across Africa are enduring power generation crises, and others will in the near future. To avoid them, some are investing billions of dollars in new coal-fired power plants that harm the environment, potentially dangerous nuclear energy projects and huge hydroelectric schemes that cut people off from water sources.

Environmentalists and clean power proponents argue that the money would be far better spent on much smaller, but ultimately further reaching, renewable energy ventures concentrated at village and town level.

A pioneer in solar energy, Bob Freling, said big, conventional power projects often benefit only urban populations, while hundreds of millions of rural Africans continue to languish in poverty caused largely by a lack of electricity.

For almost 20 years, as director of the Washington DC-based Solar Electric Light Fund (SELF) NGO, Freling has helped provide access to clean, sustainable solar energy to more than a million people in 20 developing countries.

He’s known internationally as “The man who wants to light up Africa” because of his conviction that access to electricity is a basic human right, not a privilege. Freling advises world leaders and the United Nations on development through solar power.

In 2008, Queen Noor of Jordan presented him with the King Hussein Leadership Prize in honor of his efforts to promote sustainable development, human rights, equity and peace.

The energy gap

In an interview with VOA, Freling said, “It makes me sad when I look at that satellite image of earth at night and see Africa still essentially in the dark. The fact that so much of Africa is still without electricity is a huge psychological burden for the continent. It’s also a physical burden counting against Africa’s progress.”

He maintained that lack of power leads to poor quality of life, children having no futures and to disease and death. “It prevents kids from reading and studying at night. It forces families to breathe in the carcinogenic fumes of kerosene lanterns and to suffer from the fires that are caused by kerosene lamps falling down or exploding – fires that maim and kill literally thousands of people every year.”

Without electricity, Freling explained, many Africans can’t earn money. “In terms of their economic lives, their productive day is done as soon as the sun goes down. There’s very little they can do to help grow their economy when there’s no access to power,” he said.

Without power, they can’t pump clean water, forcing them to trudge long and dangerous distances in search of water and wood for the fires needed to purify it. To do these basic chores of survival, many African children are forced to drop out of school.

“Without energy, these folks will not be able to experience significant improvements in their health and education. When you get right down to it, energy is the foundation for life,” Freling said.

Photovoltaic revolution

Freling’s NGO electrifies rural areas with what he called “stand-alone photovoltaic systems.” Arrays of solar panels use cells known as photovoltaics to convert sunlight into electrical current. A battery stores the electricity and, when discharged, powers lights and other appliances. The batteries are large enough to provide several days of electricity if overcast weather prevents recharging.

“It’s one of the most gratifying parts of my job – the reactions of people who are able to flip a switch and have electric light come on for the first time. It’s a very profound experience, for them as well as for me,” Freling said. “It’s amazing to see a whole previously unknown world of opportunity suddenly open up to them, with just one light bulb coming on. To see peoples’ faces, the sheer joy on them, when they realize that they will now be able to read at night, is indescribable.”

The SELF NGO has used microfinance arrangements to enable individual families to pay for their electricity units. A photovoltaic energy system designed for home use usually costs between $550 and $650.

Freling explained, “In the long run these solar systems work out much cheaper than people having to buy kerosene and candles every week their whole lives, and they’re safe and environmentally friendly…. Families have usually paid for them within two to three years.”

SELF initially focused on electrifying individual homes. But, in the early 2000s, Freling decided to “go bigger.”

“As much as I believe in bringing light to a family, I recognized that the technology we were using had potential way beyond household lighting, because the same solar panel that is used to light up a house can be used to pump water, or power a health clinic or a school.”

So in recent years SELF has concentrated on powering entire villages across Africa – revolutionizing life for many thousands of people.

Northern Nigerian example

The NGO’s flagship “whole village” project is in northern Nigeria. The country’s vast oil wealth hasn’t benefited the region’s inhabitants. Most don’t have electricity. They live in mud and thatch homes and survive by growing crops among desert grasslands. They cook over wood fires; kerosene lamps provide light; and clean water sources are far away.

But SELF’s solar technology has transformed the lives of 7,500 people in northern Nigeria. “We electrified three villages in the northern state of Jigawa and in each of the villages provided power for a number of homes, a school, a health clinic, a mosque, water pumping systems, street lighting, and even a microenterprise center that would power a number of small businesses in the village,” Freling explained.

Businesses selling food have sprung up under streetlights, and people are earning money for the first time in their lives. Illiterate adults are learning to read and write at night classes. Children have access to computers – a previously unattainable but vital part of modern education.

As in other countries, like Burundi, Lesotho, Malawi and Rwanda, the photovoltaic solar energy provided by SELF has for the first time electrified clinics. In Jigawa, doctors are now able to treat patients at night, and vaccines can be refrigerated – allowing more children to be vaccinated against potentially fatal sicknesses and facilitating round-the-clock treatment of people with serious diseases such as HIV, malaria and cholera.

African creativity

Something happened in one of the Nigerian villages that Freling said illustrated the “supreme ingenuity” of Africans that he’s come to respect over the years.

At Wawan-rafi, farmers irrigate their crops with water from a river. Traditionally they’ve watered their fields using hollow gourds – a very slow and labor intensive process that limited production severely.

“It was one of the villagers who came up with the idea of putting an array of solar panels on the back of a cow. The villagers wanted something that was portable,” said Freling.

So, in cooperation with the people of Wawan-rafi, SELF designed a cattle cart equipped with fold-out solar modules of extreme strength that could power a water pump and be moved from field to field. It allows farmers to irrigate their crops efficiently and grow much more food than ever before.

Freling said, “We want to work with the community to come up with solutions that meet their needs. They’re very intelligent; they’ve very creative people. You give them half a chance and I can assure you they will come up with very innovative solutions. They just need a little bit of help.”

He maintained that access to electricity that allows development fosters peace, especially in areas prone to religious and political extremism, such as northern Nigeria.

“When you have people who are deprived of basic opportunities in life, they become disenfranchised. Often, those vacuums can be filled by people promising certain things. The more you can provide a better life for people in developing countries, the better chance we have of preventing them from being attracted to extremist organizations [like al-Qaeda affiliated Boko Haram in Nigeria],” said Freling. “I think that one of the greatest antidotes to this kind of terrorism is to make life better for people.”

Unique irrigation in Benin

In the Kalalé district of northern Benin, more than 100,000 people live in 44 villages. Before SELF entered the area, none of the inhabitants had electricity. There are also no schools or hospitals there. But the villagers’ main concern is chronic food shortages.

Kalalé borders the arid Sahel region and has a very long dry season. Freling recalled his first visit to the district in 2007. “Essentially no food was grown; diets were very restricted; malnutrition was widespread. You’d often see these kids with the distended belly, a telltale sign of kwashiorkor, a form of malnutrition.”

SELF implemented a groundbreaking method to end food insecurity in the area. “We combined solar water pumping with drip irrigation, allowing farmers to grow food year round,” said Freling.

Drip irrigation systems use gravity to draw water from reservoirs through pipes. But power is needed to pump water to the reservoirs. Usually, the power is provided by diesel engines, but Freling wanted the system in Benin to be environmentally “clean” and energized by the sun.

SELF’s “Solar Market Garden” prototype was successful. A solar pump now draws water from a stream that flows constantly to fill an irrigation dam in the Bessassi area. At Dunkassa village, water is pumped from the ground.

Freling described the project as a remarkable success. “You go back and you see these fields filled with leafy green vegetables…. What I noticed the first time I went back was how the women had physically filled out. You could visibly see a difference in the health of the people in the village. They were eating well.”

Three Solar Market Gardens enabled the villages of Bessassi and Dunkassa to produce almost two tons of fresh produce every month. “For the first time in their lives, they weren’t hungry. On top of that, they were making money. I would say about 20 percent of the produce was being consumed by the [local] families, the rest was being sold to market,” said Freling.

As well as feeding them, the electricity that allowed the villagers to irrigate their crops opened up the world of business to them. Suddenly, said Freling, they could afford clothes for themselves and their children and medicines without which death rates had previously spiked.

Costs and training

According to Freling, a Solar Market Garden - sometimes including photovoltaic power systems - managed by a village collective typically costs about $25,000. “That sounds like a lot but they pay for themselves within a few years [through profits made from having access to power],” he said. “We’ve been able to demonstrate in many places in Africa how much cheaper it is to provide electricity with solar power rather than traditional diesel generators.”

Freling explained that while the upfront cost of a generator is low, its operating and maintenance costs are high, with spare parts being expensive and rare in many parts of Africa. He added that diesel fuel is often not available in isolated regions of the continent.

He continued, “With photovoltaics, the upfront cost is higher but there are no fuel costs and much less maintenance costs. So over time you’ll spend a lot less money on these solar systems.”

SELF ensures that communities have thorough knowledge of the solar energy systems they use. Its experts help locals design, install and maintain the technology. Freling said they’ve trained many Africans as solar technicians.

“We’ve had great luck in finding people – in some cases with no more than a fourth, fifth grade education – but they’re smart, they’re intuitive, they’re good with their hands and they become great solar technicians. We’re very proud of some of the folks that we’ve been able to train in Africa to become solar champions in their own right,” he said.

MDGs to fail without electricity

Freling and his organization have done plenty to bring electricity to Africa. But he said the many millions of Africans who continue to “decay in the dark” now need help from figures far more powerful than he.

“I am very, very impatient for the continent to make a commitment to bring in modern clean energy services to the people. It’s within our power now. But a lot depends on the political will of African leaders. That will be the most important determining factor in whether or not African populations have access to energy,” he said.

Freling called for a new level of commitment from African leaders, for them to “embrace the idea of universal energy access” and to recognize that having electricity is a basic human right.

He urged the leaders to make the political commitments necessary to put in place the regulatory, legal and financial environments needed for the private sector, civil society and local governments “to cooperate towards creative solutions that will enable people to have access to clean energy services.”

Without the large-scale “green” electrification of the developing world, Freling warned, each of the U.N.’s eight Millennium Development Goals – including the end of poverty, hunger, widespread death from disease and lack of education – will fail.

Countries across Africa are enduring power generation crises, and others will in the near future. To avoid them, some are investing billions of dollars in new coal-fired power plants that harm the environment, potentially dangerous nuclear energy projects and huge hydroelectric schemes that cut people off from water sources.

Environmentalists and clean power proponents argue that the money would be far better spent on much smaller, but ultimately further reaching, renewable energy ventures concentrated at village and town level.

A pioneer in solar energy, Bob Freling, said big, conventional power projects often benefit only urban populations, while hundreds of millions of rural Africans continue to languish in poverty caused largely by a lack of electricity.

For almost 20 years, as director of the Washington DC-based Solar Electric Light Fund (SELF) NGO, Freling has helped provide access to clean, sustainable solar energy to more than a million people in 20 developing countries.

He’s known internationally as “The man who wants to light up Africa” because of his conviction that access to electricity is a basic human right, not a privilege. Freling advises world leaders and the United Nations on development through solar power.

In 2008, Queen Noor of Jordan presented him with the King Hussein Leadership Prize in honor of his efforts to promote sustainable development, human rights, equity and peace.

The energy gap

In an interview with VOA, Freling said, “It makes me sad when I look at that satellite image of earth at night and see Africa still essentially in the dark. The fact that so much of Africa is still without electricity is a huge psychological burden for the continent. It’s also a physical burden counting against Africa’s progress.”

He maintained that lack of power leads to poor quality of life, children having no futures and to disease and death. “It prevents kids from reading and studying at night. It forces families to breathe in the carcinogenic fumes of kerosene lanterns and to suffer from the fires that are caused by kerosene lamps falling down or exploding – fires that maim and kill literally thousands of people every year.”

Without electricity, Freling explained, many Africans can’t earn money. “In terms of their economic lives, their productive day is done as soon as the sun goes down. There’s very little they can do to help grow their economy when there’s no access to power,” he said.

Without power, they can’t pump clean water, forcing them to trudge long and dangerous distances in search of water and wood for the fires needed to purify it. To do these basic chores of survival, many African children are forced to drop out of school.

“Without energy, these folks will not be able to experience significant improvements in their health and education. When you get right down to it, energy is the foundation for life,” Freling said.

Photovoltaic revolution

Freling’s NGO electrifies rural areas with what he called “stand-alone photovoltaic systems.” Arrays of solar panels use cells known as photovoltaics to convert sunlight into electrical current. A battery stores the electricity and, when discharged, powers lights and other appliances. The batteries are large enough to provide several days of electricity if overcast weather prevents recharging.

“It’s one of the most gratifying parts of my job – the reactions of people who are able to flip a switch and have electric light come on for the first time. It’s a very profound experience, for them as well as for me,” Freling said. “It’s amazing to see a whole previously unknown world of opportunity suddenly open up to them, with just one light bulb coming on. To see peoples’ faces, the sheer joy on them, when they realize that they will now be able to read at night, is indescribable.”

The SELF NGO has used microfinance arrangements to enable individual families to pay for their electricity units. A photovoltaic energy system designed for home use usually costs between $550 and $650.

Freling explained, “In the long run these solar systems work out much cheaper than people having to buy kerosene and candles every week their whole lives, and they’re safe and environmentally friendly…. Families have usually paid for them within two to three years.”

SELF initially focused on electrifying individual homes. But, in the early 2000s, Freling decided to “go bigger.”

“As much as I believe in bringing light to a family, I recognized that the technology we were using had potential way beyond household lighting, because the same solar panel that is used to light up a house can be used to pump water, or power a health clinic or a school.”

So in recent years SELF has concentrated on powering entire villages across Africa – revolutionizing life for many thousands of people.

Northern Nigerian example

The NGO’s flagship “whole village” project is in northern Nigeria. The country’s vast oil wealth hasn’t benefited the region’s inhabitants. Most don’t have electricity. They live in mud and thatch homes and survive by growing crops among desert grasslands. They cook over wood fires; kerosene lamps provide light; and clean water sources are far away.

But SELF’s solar technology has transformed the lives of 7,500 people in northern Nigeria. “We electrified three villages in the northern state of Jigawa and in each of the villages provided power for a number of homes, a school, a health clinic, a mosque, water pumping systems, street lighting, and even a microenterprise center that would power a number of small businesses in the village,” Freling explained.

Businesses selling food have sprung up under streetlights, and people are earning money for the first time in their lives. Illiterate adults are learning to read and write at night classes. Children have access to computers – a previously unattainable but vital part of modern education.

As in other countries, like Burundi, Lesotho, Malawi and Rwanda, the photovoltaic solar energy provided by SELF has for the first time electrified clinics. In Jigawa, doctors are now able to treat patients at night, and vaccines can be refrigerated – allowing more children to be vaccinated against potentially fatal sicknesses and facilitating round-the-clock treatment of people with serious diseases such as HIV, malaria and cholera.

African creativity

Something happened in one of the Nigerian villages that Freling said illustrated the “supreme ingenuity” of Africans that he’s come to respect over the years.

At Wawan-rafi, farmers irrigate their crops with water from a river. Traditionally they’ve watered their fields using hollow gourds – a very slow and labor intensive process that limited production severely.

“It was one of the villagers who came up with the idea of putting an array of solar panels on the back of a cow. The villagers wanted something that was portable,” said Freling.

So, in cooperation with the people of Wawan-rafi, SELF designed a cattle cart equipped with fold-out solar modules of extreme strength that could power a water pump and be moved from field to field. It allows farmers to irrigate their crops efficiently and grow much more food than ever before.

Freling said, “We want to work with the community to come up with solutions that meet their needs. They’re very intelligent; they’ve very creative people. You give them half a chance and I can assure you they will come up with very innovative solutions. They just need a little bit of help.”

He maintained that access to electricity that allows development fosters peace, especially in areas prone to religious and political extremism, such as northern Nigeria.

“When you have people who are deprived of basic opportunities in life, they become disenfranchised. Often, those vacuums can be filled by people promising certain things. The more you can provide a better life for people in developing countries, the better chance we have of preventing them from being attracted to extremist organizations [like al-Qaeda affiliated Boko Haram in Nigeria],” said Freling. “I think that one of the greatest antidotes to this kind of terrorism is to make life better for people.”

Unique irrigation in Benin

In the Kalalé district of northern Benin, more than 100,000 people live in 44 villages. Before SELF entered the area, none of the inhabitants had electricity. There are also no schools or hospitals there. But the villagers’ main concern is chronic food shortages.

Kalalé borders the arid Sahel region and has a very long dry season. Freling recalled his first visit to the district in 2007. “Essentially no food was grown; diets were very restricted; malnutrition was widespread. You’d often see these kids with the distended belly, a telltale sign of kwashiorkor, a form of malnutrition.”

SELF implemented a groundbreaking method to end food insecurity in the area. “We combined solar water pumping with drip irrigation, allowing farmers to grow food year round,” said Freling.

Drip irrigation systems use gravity to draw water from reservoirs through pipes. But power is needed to pump water to the reservoirs. Usually, the power is provided by diesel engines, but Freling wanted the system in Benin to be environmentally “clean” and energized by the sun.

SELF’s “Solar Market Garden” prototype was successful. A solar pump now draws water from a stream that flows constantly to fill an irrigation dam in the Bessassi area. At Dunkassa village, water is pumped from the ground.

Freling described the project as a remarkable success. “You go back and you see these fields filled with leafy green vegetables…. What I noticed the first time I went back was how the women had physically filled out. You could visibly see a difference in the health of the people in the village. They were eating well.”

Three Solar Market Gardens enabled the villages of Bessassi and Dunkassa to produce almost two tons of fresh produce every month. “For the first time in their lives, they weren’t hungry. On top of that, they were making money. I would say about 20 percent of the produce was being consumed by the [local] families, the rest was being sold to market,” said Freling.

As well as feeding them, the electricity that allowed the villagers to irrigate their crops opened up the world of business to them. Suddenly, said Freling, they could afford clothes for themselves and their children and medicines without which death rates had previously spiked.

Costs and training

According to Freling, a Solar Market Garden - sometimes including photovoltaic power systems - managed by a village collective typically costs about $25,000. “That sounds like a lot but they pay for themselves within a few years [through profits made from having access to power],” he said. “We’ve been able to demonstrate in many places in Africa how much cheaper it is to provide electricity with solar power rather than traditional diesel generators.”

Freling explained that while the upfront cost of a generator is low, its operating and maintenance costs are high, with spare parts being expensive and rare in many parts of Africa. He added that diesel fuel is often not available in isolated regions of the continent.

He continued, “With photovoltaics, the upfront cost is higher but there are no fuel costs and much less maintenance costs. So over time you’ll spend a lot less money on these solar systems.”

SELF ensures that communities have thorough knowledge of the solar energy systems they use. Its experts help locals design, install and maintain the technology. Freling said they’ve trained many Africans as solar technicians.

“We’ve had great luck in finding people – in some cases with no more than a fourth, fifth grade education – but they’re smart, they’re intuitive, they’re good with their hands and they become great solar technicians. We’re very proud of some of the folks that we’ve been able to train in Africa to become solar champions in their own right,” he said.

MDGs to fail without electricity

Freling and his organization have done plenty to bring electricity to Africa. But he said the many millions of Africans who continue to “decay in the dark” now need help from figures far more powerful than he.

“I am very, very impatient for the continent to make a commitment to bring in modern clean energy services to the people. It’s within our power now. But a lot depends on the political will of African leaders. That will be the most important determining factor in whether or not African populations have access to energy,” he said.

Freling called for a new level of commitment from African leaders, for them to “embrace the idea of universal energy access” and to recognize that having electricity is a basic human right.

He urged the leaders to make the political commitments necessary to put in place the regulatory, legal and financial environments needed for the private sector, civil society and local governments “to cooperate towards creative solutions that will enable people to have access to clean energy services.”

Without the large-scale “green” electrification of the developing world, Freling warned, each of the U.N.’s eight Millennium Development Goals – including the end of poverty, hunger, widespread death from disease and lack of education – will fail.

Environmentalists and clean power proponents argue that the money would be far better spent on much smaller, but ultimately further reaching, renewable energy ventures concentrated at village and town level.

A pioneer in solar energy, Bob Freling, said big, conventional power projects often benefit only urban populations, while hundreds of millions of rural Africans continue to languish in poverty caused largely by a lack of electricity.

For almost 20 years, as director of the Washington DC-based Solar Electric Light Fund (SELF) NGO, Freling has helped provide access to clean, sustainable solar energy to more than a million people in 20 developing countries.

He’s known internationally as “The man who wants to light up Africa” because of his conviction that access to electricity is a basic human right, not a privilege. Freling advises world leaders and the United Nations on development through solar power.

In 2008, Queen Noor of Jordan presented him with the King Hussein Leadership Prize in honor of his efforts to promote sustainable development, human rights, equity and peace.

The energy gap

In an interview with VOA, Freling said, “It makes me sad when I look at that satellite image of earth at night and see Africa still essentially in the dark. The fact that so much of Africa is still without electricity is a huge psychological burden for the continent. It’s also a physical burden counting against Africa’s progress.”

He maintained that lack of power leads to poor quality of life, children having no futures and to disease and death. “It prevents kids from reading and studying at night. It forces families to breathe in the carcinogenic fumes of kerosene lanterns and to suffer from the fires that are caused by kerosene lamps falling down or exploding – fires that maim and kill literally thousands of people every year.”

Without electricity, Freling explained, many Africans can’t earn money. “In terms of their economic lives, their productive day is done as soon as the sun goes down. There’s very little they can do to help grow their economy when there’s no access to power,” he said.

Without power, they can’t pump clean water, forcing them to trudge long and dangerous distances in search of water and wood for the fires needed to purify it. To do these basic chores of survival, many African children are forced to drop out of school.

“Without energy, these folks will not be able to experience significant improvements in their health and education. When you get right down to it, energy is the foundation for life,” Freling said.

Photovoltaic revolution

Freling’s NGO electrifies rural areas with what he called “stand-alone photovoltaic systems.” Arrays of solar panels use cells known as photovoltaics to convert sunlight into electrical current. A battery stores the electricity and, when discharged, powers lights and other appliances. The batteries are large enough to provide several days of electricity if overcast weather prevents recharging.

“It’s one of the most gratifying parts of my job – the reactions of people who are able to flip a switch and have electric light come on for the first time. It’s a very profound experience, for them as well as for me,” Freling said. “It’s amazing to see a whole previously unknown world of opportunity suddenly open up to them, with just one light bulb coming on. To see peoples’ faces, the sheer joy on them, when they realize that they will now be able to read at night, is indescribable.”

The SELF NGO has used microfinance arrangements to enable individual families to pay for their electricity units. A photovoltaic energy system designed for home use usually costs between $550 and $650.

Freling explained, “In the long run these solar systems work out much cheaper than people having to buy kerosene and candles every week their whole lives, and they’re safe and environmentally friendly…. Families have usually paid for them within two to three years.”

SELF initially focused on electrifying individual homes. But, in the early 2000s, Freling decided to “go bigger.”

“As much as I believe in bringing light to a family, I recognized that the technology we were using had potential way beyond household lighting, because the same solar panel that is used to light up a house can be used to pump water, or power a health clinic or a school.”

So in recent years SELF has concentrated on powering entire villages across Africa – revolutionizing life for many thousands of people.

Northern Nigerian example

The NGO’s flagship “whole village” project is in northern Nigeria. The country’s vast oil wealth hasn’t benefited the region’s inhabitants. Most don’t have electricity. They live in mud and thatch homes and survive by growing crops among desert grasslands. They cook over wood fires; kerosene lamps provide light; and clean water sources are far away.

But SELF’s solar technology has transformed the lives of 7,500 people in northern Nigeria. “We electrified three villages in the northern state of Jigawa and in each of the villages provided power for a number of homes, a school, a health clinic, a mosque, water pumping systems, street lighting, and even a microenterprise center that would power a number of small businesses in the village,” Freling explained.

Businesses selling food have sprung up under streetlights, and people are earning money for the first time in their lives. Illiterate adults are learning to read and write at night classes. Children have access to computers – a previously unattainable but vital part of modern education.

As in other countries, like Burundi, Lesotho, Malawi and Rwanda, the photovoltaic solar energy provided by SELF has for the first time electrified clinics. In Jigawa, doctors are now able to treat patients at night, and vaccines can be refrigerated – allowing more children to be vaccinated against potentially fatal sicknesses and facilitating round-the-clock treatment of people with serious diseases such as HIV, malaria and cholera.

African creativity

Something happened in one of the Nigerian villages that Freling said illustrated the “supreme ingenuity” of Africans that he’s come to respect over the years.

At Wawan-rafi, farmers irrigate their crops with water from a river. Traditionally they’ve watered their fields using hollow gourds – a very slow and labor intensive process that limited production severely.

“It was one of the villagers who came up with the idea of putting an array of solar panels on the back of a cow. The villagers wanted something that was portable,” said Freling.

So, in cooperation with the people of Wawan-rafi, SELF designed a cattle cart equipped with fold-out solar modules of extreme strength that could power a water pump and be moved from field to field. It allows farmers to irrigate their crops efficiently and grow much more food than ever before.

Freling said, “We want to work with the community to come up with solutions that meet their needs. They’re very intelligent; they’ve very creative people. You give them half a chance and I can assure you they will come up with very innovative solutions. They just need a little bit of help.”

He maintained that access to electricity that allows development fosters peace, especially in areas prone to religious and political extremism, such as northern Nigeria.

“When you have people who are deprived of basic opportunities in life, they become disenfranchised. Often, those vacuums can be filled by people promising certain things. The more you can provide a better life for people in developing countries, the better chance we have of preventing them from being attracted to extremist organizations [like al-Qaeda affiliated Boko Haram in Nigeria],” said Freling. “I think that one of the greatest antidotes to this kind of terrorism is to make life better for people.”

Unique irrigation in Benin

In the Kalalé district of northern Benin, more than 100,000 people live in 44 villages. Before SELF entered the area, none of the inhabitants had electricity. There are also no schools or hospitals there. But the villagers’ main concern is chronic food shortages.

Kalalé borders the arid Sahel region and has a very long dry season. Freling recalled his first visit to the district in 2007. “Essentially no food was grown; diets were very restricted; malnutrition was widespread. You’d often see these kids with the distended belly, a telltale sign of kwashiorkor, a form of malnutrition.”

SELF implemented a groundbreaking method to end food insecurity in the area. “We combined solar water pumping with drip irrigation, allowing farmers to grow food year round,” said Freling.

Drip irrigation systems use gravity to draw water from reservoirs through pipes. But power is needed to pump water to the reservoirs. Usually, the power is provided by diesel engines, but Freling wanted the system in Benin to be environmentally “clean” and energized by the sun.

SELF’s “Solar Market Garden” prototype was successful. A solar pump now draws water from a stream that flows constantly to fill an irrigation dam in the Bessassi area. At Dunkassa village, water is pumped from the ground.

Freling described the project as a remarkable success. “You go back and you see these fields filled with leafy green vegetables…. What I noticed the first time I went back was how the women had physically filled out. You could visibly see a difference in the health of the people in the village. They were eating well.”

Three Solar Market Gardens enabled the villages of Bessassi and Dunkassa to produce almost two tons of fresh produce every month. “For the first time in their lives, they weren’t hungry. On top of that, they were making money. I would say about 20 percent of the produce was being consumed by the [local] families, the rest was being sold to market,” said Freling.

As well as feeding them, the electricity that allowed the villagers to irrigate their crops opened up the world of business to them. Suddenly, said Freling, they could afford clothes for themselves and their children and medicines without which death rates had previously spiked.

Costs and training

According to Freling, a Solar Market Garden - sometimes including photovoltaic power systems - managed by a village collective typically costs about $25,000. “That sounds like a lot but they pay for themselves within a few years [through profits made from having access to power],” he said. “We’ve been able to demonstrate in many places in Africa how much cheaper it is to provide electricity with solar power rather than traditional diesel generators.”

Freling explained that while the upfront cost of a generator is low, its operating and maintenance costs are high, with spare parts being expensive and rare in many parts of Africa. He added that diesel fuel is often not available in isolated regions of the continent.

He continued, “With photovoltaics, the upfront cost is higher but there are no fuel costs and much less maintenance costs. So over time you’ll spend a lot less money on these solar systems.”

SELF ensures that communities have thorough knowledge of the solar energy systems they use. Its experts help locals design, install and maintain the technology. Freling said they’ve trained many Africans as solar technicians.

“We’ve had great luck in finding people – in some cases with no more than a fourth, fifth grade education – but they’re smart, they’re intuitive, they’re good with their hands and they become great solar technicians. We’re very proud of some of the folks that we’ve been able to train in Africa to become solar champions in their own right,” he said.

MDGs to fail without electricity

Freling and his organization have done plenty to bring electricity to Africa. But he said the many millions of Africans who continue to “decay in the dark” now need help from figures far more powerful than he.

“I am very, very impatient for the continent to make a commitment to bring in modern clean energy services to the people. It’s within our power now. But a lot depends on the political will of African leaders. That will be the most important determining factor in whether or not African populations have access to energy,” he said.

Freling called for a new level of commitment from African leaders, for them to “embrace the idea of universal energy access” and to recognize that having electricity is a basic human right.

He urged the leaders to make the political commitments necessary to put in place the regulatory, legal and financial environments needed for the private sector, civil society and local governments “to cooperate towards creative solutions that will enable people to have access to clean energy services.”

Without the large-scale “green” electrification of the developing world, Freling warned, each of the U.N.’s eight Millennium Development Goals – including the end of poverty, hunger, widespread death from disease and lack of education – will fail.

Just received a check for $500.

ReplyDeleteSometimes people don't believe me when I tell them about how much money you can earn filling out paid surveys online...

So I took a video of myself actually getting paid $500 for filling paid surveys to set the record straight once and for all.